RethinkDB internals: Patching for fun and throughput

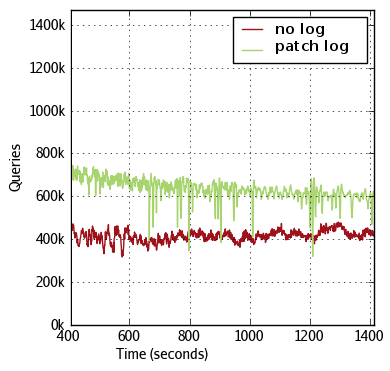

A central challenge in developing a high performance database is to maximize the efficiency at which hardware resources are used. By implementing a new optimization in how RethinkDB handles disk writes - the patch log - we were able to achieve an additional 50% increase in query throughput. The following graph compares the sustainable performance of RethinkDB for a mixed read/write workload (roughly 10% write operations) with and without the patch log. In both cases we configured the system to be bound by the disks’ write bandwidth.

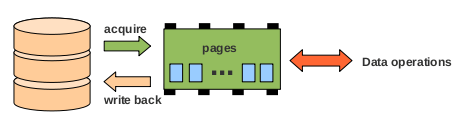

Like most databases, RethinkDB uses an in-memory page cache to allow for efficient data processing. Modifying a data block involves the following steps:

- check if the block is in the page cache

- if the block is not in the cache: acquire the block from disk

- perform the actual modification on the in-memory page

- mark the page “dirty”

Eventually the page cache will fill up, so no more data blocks can be acquired unless space is freed. This requires evicting pages from the page cache. However, some of the pages might have been modified. To preserve these modifications, pages marked as “dirty” must be written back to disk. There are different approaches to when such a write-back should happen. In RethinkDB, we write data back periodically, and trigger an immediate write-back whenever the number of dirty pages in the page cache exceeds some limit.

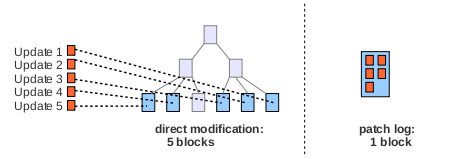

Now, there is one problem with this approach: Consider five updates which set five different rows/keys to new values. RethinkDB uses a B-tree data structure to organize data internally; most databases use similar tree data structures to index and/or store data. As a consequence, updates to five random keys have a good chance of affecting five different parts of the tree. This has consequences for the next write-back. Even minor modifications to five different keys involve writing five complete blocks to disk. Depending on the workload, this can easily lead to a saturation of disk write throughput, which in turn limits the overall database performance as data from the page cache cannot be evicted fast enough.

RethinkDB tackles this problem by using a system of serializable page patches. A patch is a data structure representing a certain modification to a block. Patches can operate on different layers of the database. On lower levels we use patches that replace a chunk of data in a page or move data around. On higher levels we have patches which insert a key/value pair into a leaf node of the B-tree or remove one.

The basic idea is to reserve some space for a “patch log” in the database. To come back to our previous example: using patches, the changes made by our five update operations can be stored much more efficiently. For smaller updates, all required patches may well fit into a single block. Instead of writing all five affected data pages back to disk, we simply write five small patches to the patch log. At this point, we have reduced the required disk write throughput by a factor of five.

Of course things are not as simple as that. Eventually our reserved log space will fill up. To free up space, we now have to apply some of the patches to the affected pages and rewrite the actual data blocks. It seems like we have just delayed the work of writing back data by using the patch log. Even worse, we spent additional time for writing the patches.

Happily another effect kicks in to save us: the patch log has aggregated patches over a long period of time. Chances are, additional updates have been performed in the same data blocks as the first five updates. This allows us to batch multiple updates for the block into a single write-back. The overall efficiency of the log depends on its size and the size of the subset of data in the database that is frequently modified. Additionally, a great boost in efficiency can be achieved by carefully tuning the decision of whether to write a patch or to rewrite the affected block instead. We have implemented automated tuning logic to guarantee low overhead and great write throughput across a wide range of workloads without any need for manual configuration.

There is one last part which we have not covered so far: When acquiring a block from disk, it must be guaranteed that the in-memory page for that block always reflects the latest changes. Specifically, this means that patches with changes that have not made it into the actual on-disk block yet must be replayed when acquiring the block. To make this fast, we load all on-disk patches into an efficient in-memory data structure when starting up the database. As the size of the patch log is limited, this only consumes a small amount of main memory. Therefore we just have to check the in-memory log data structure to decide whether patches have to be applied. To replay only the subset of patches which have not yet been applied to the on-disk data block, a sequential “transaction id” is stored in the block whenever a block gets written back to disk. Each patch on the other hand contains the transaction id to which it applies. If the block’s transaction id is higher than the one of some patch, the patch is already reflected in the block’s data and must not be replayed again.

Overall, the patch log turns out to be a powerful technique for optimizing the translation of in-memory data modifications to disk writes. According to our benchmarks, it allows for significant performance increases both when writing to SSDs and rotational drives.

RethinkDB Team

RethinkDB Team