On TRIM, NCQ, and Write Amplification

Alex Popescu wrote a blog post asking some questions about RethinkDB and SSD performance. There is a related Twitter conversation happening here. There are two fundamental questions:

- In which cases does SSD performance begin to degrade over time?

- How does the TRIM command affect performance degradation?

The questions are very deep and I cannot do them justice in a single blog post, but I decided to post a quick write-up as a start.

Flash basics

Flash memory has physical properties that prevent overwriting a data block directly. Before new version of the data can be written, a special ERASE command must be called on the block. Erasing a block is significantly slower than writing to a block that has already been erased, so when software tries to overwrite a block of data, SSD drives automatically write the new block to a pre-erased area, and erase obsolete blocks in the background. This technology (usually referred to as Flash Translation Layer) allows for fast write performance on modern SSDs.

There are two complications associated with erasing blocks. The first is that flash memory only allows erasing relatively large block sizes (128KB and above). This means that if there is a significant fragmentation on the drive, before a block can be erased, live data must be copied to a different location on the drive. The rate at which this happened is called write amplification factor. Write amplification negatively affects write performance because out of a fixed number of write operations that can be done per second, some number of operations must be spent on copying data within the drive. The higher the internal fragmentation (and therefore write amplification), the lower the perceived performance of the drive.

The second complication is that SSD drives often lack sufficient information to determine whether a particular block is no longer useful. Consider a file system where many 4KB files are created and soon deleted. If the file system reuses space (i.e. places new 4KB files on the same block device locations where the deleted files used to be), SSD drives will write the file to a different physical location to avoid a slow ERASE command, but will note that the old space no longer contains useful data. However, if the file system does not reuse space and places every new file onto a new block device location, there is no way for the drive to know that the old file has been erased. If the workload persists for a considerable amount of time, from the point of view of the SSD drive, most flash space will soon be filled, and the drive will no longer be able to efficiently remap writes and run erase in the background - it will be forced to do a slow erase command for every write, killing performance.

The TRIM command

In order to get around the second issue, SSD drives and most modern operating systems support a TRIM command. Sending the TRIM command to the drive lets it know that the given interval of the block device is no longer in use. This lets the drive garbage collect the data and continue running its translation algorithms efficiently.

An additional problem is that the TRIM command comes with a penalty. Modern SSD drives are parallelized devices that allow performing multiple operations in parallel. In order to get peak efficiency, multiple concurrent requests have to be sent to the drive. This happens via a Native Command Queuing protocol (or NCQ). Modern drives can run up to 31 commands concurrently and often achieve peak performance when there are close to 31 commands in the pipeline. The problem with TRIM is that on many interfaces it requires stalling the NCQ pipeline. That is, when a TRIM command is issued, all 31 commands must be finished while no other commands can go in. Then the TRIM command goes into the drive, and then the pipeline of traditional read and write commands accumulates again.

This is not a big issue on desktop systems where TRIM can be sent during idle time, but it is a huge problem on server systems that do not encounter much idle time. It’s possible to get around this issue by grouping blocks that can be trimmed and sending fewer TRIM commands for larger blocks, but this makes disk layout significantly more complicated. For this reason most systems don’t use the explicit TRIM command in server-grade environments. Instead, it’s much more efficient to lay out the data in a way where the drive can figure out which data is no longer useful implicitly.

Performance

So, the performance issues are not related to TRIM, and have much more to do with internal fragmentation of the drive over time. If special care is not taken to layout the data in a certain way, performance degradation will always happen for write-heavy workloads with little idle time (which is a very common scenario in server environments). This is not database specific and will happen for file systems in exactly the same way.

RethinkDB internals

RethinkDB gets around these issues in the following way. We identified over a dozen parameters that affect the performance of any given drive (for example, block size, stride, timing, etc.) We have a benchmarking engine that treats the underlying storage system as a black box and brute forces through many hundreds of permutations of these parameters to find an ideal workload for the underlying drive.

We’ve also built a transformation engine that converts the user workload on the database into the ideal workload for the underlying drive. For example, if you modify the same row (and therefore, the same B-Tree block) twice, our transformation engine may decide to write the second block into the same location as the first one, a location right next to it, a completely different location, etc. For every drive we test, we take the ideal parameters for that drive and feed them back into the production system. This lets us get up to a factor of ten performance improvement in the number of write operations per second we can push through a drive. This happens by a combination of “implicit TRIM”, and a number of emergent properties of the drive that our benchmarking engine discovers. We can benchmark a given drive very quickly by treating it as a black box, instead of spending months or years reverse engineering the behavior of every drive on the market.

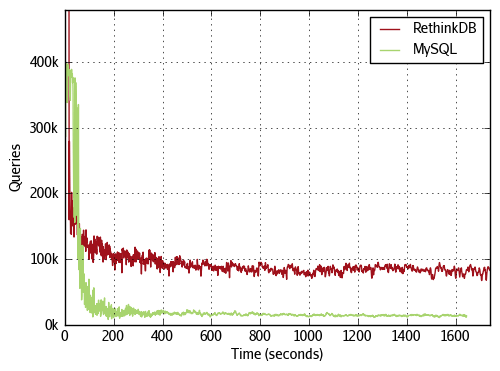

Here is a graph for an IO bound workload run on a commonly used SSD drive. The workload is heavily biased towards reads (the ratio is roughly 4:1), but still does enough writes to gain significant performance improvements from the disk.

Slava Akhmechet

Slava Akhmechet