Making coroutines fast

Previously, I wrote about using coroutines in RethinkDB. Coroutines are a nice alternative to callbacks because they are easier to program in, and they are a nice alternative to threads because of their greater performance. But how fast are they?

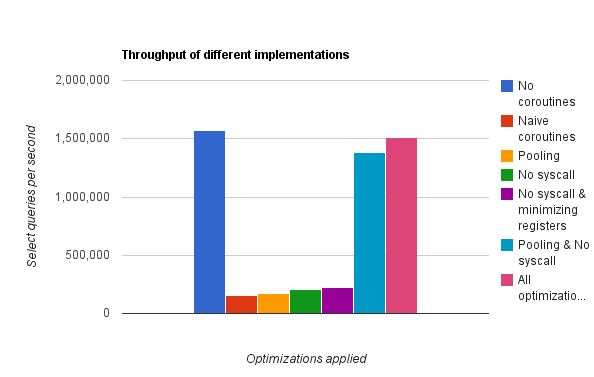

Just using an off-the-shelf library like libcoroutine isn’t as fast as you might think. The graph below shows the huge performance degradation of a naive implementation of coroutines (the short red bar) compared to the old callback- based code (the blue bar on the left). But with the right set of optimizations, we can recover a level of performance about equal to the non- coroutine version. With these optimizations, throughput is recorded as the pink bar on the right, which is within the margin of error of the original version.

The improvement comes from two optimizations: reuse of stacks and a lightweight

swapcontext implementation. The two optimizations are completely internal to

the coroutines library and require no changes to code which uses them. As you

can see from the graph, both optimizations are essential for acceptable

performance.

Reusing coroutines

Spawning a new coroutine with libcoroutine on Unix issues the following actions:

- A stack is allocated

- A

ucontextobject is allocated and initialized usingmakecontextandgetcontext - A libcoroutine

Coroobject is created around the stack and context - The context is swapped to the new coroutine, jumping to a trampoline, and from there, executing user code with supplied arguments.

When the user code terminates, all of these structures have to be deallocated. Unless our allocator is perfect (which it isn’t) and the ucontext routines are really fast (which they aren’t), this constitutes a lot of waste since each select request issues multiple coroutines. Why not reuse the same coroutine object for multiple actions?

The logic is simple. Each OS thread has a list of free coroutines. To do something in a new coroutine, the user pops an item off the free list and sends it a message containing the action. Each coroutine has a ‘run loop’ which does the following:

- Wait for a message containing an action

- Execute that action

- Push self back on to the free list

If a coroutine is requested and the free list is empty, a new coroutine executing that run loop is spawned and pushed onto the list.

A lightweight swapcontext implementation

Once old coroutines are reused, the only frequent call into libcoroutine that

gets made is switching contexts. Ultimately, this calls the ucontext routine

swapcontext. What does that do exactly? Well, here’s the glibc 2.12.2

implementation for x86-64:

swapcontext:

/* Save the preserved registers, the registers used for passing args,

and the return address. */

movq %rbx, oRBX(%rdi)

movq %rbp, oRBP(%rdi)

movq %r12, oR12(%rdi)

movq %r13, oR13(%rdi)

movq %r14, oR14(%rdi)

movq %r15, oR15(%rdi)

movq %rdi, oRDI(%rdi)

movq %rsi, oRSI(%rdi)

movq %rdx, oRDX(%rdi)

movq %rcx, oRCX(%rdi)

movq %r8, oR8(%rdi)

movq %r9, oR9(%rdi)

movq (%rsp), %rcx

movq %rcx, oRIP(%rdi)

leaq 8(%rsp), %rcx /* Exclude the return address. */

movq %rcx, oRSP(%rdi)

/* We have separate floating-point register content memory on the

stack. We use the __fpregs_mem block in the context. Set the

links up correctly. */

leaq oFPREGSMEM(%rdi), %rcx

movq %rcx, oFPREGS(%rdi)

/* Save the floating-point environment. */

fnstenv (%rcx)

stmxcsr oMXCSR(%rdi)

/* The syscall destroys some registers, save them. */

movq %rsi, %r12

/* Save the current signal mask and install the new one with

rt_sigprocmask (SIG_BLOCK, newset, oldset,_NSIG/8). */

leaq oSIGMASK(%rdi), %rdx

leaq oSIGMASK(%rsi), %rsi

movl $SIG_SETMASK, %edi

movl $_NSIG8,%r10d

movl $__NR_rt_sigprocmask, %eax

syscall

cmpq $-4095, %rax /* Check %rax for error. */

jae SYSCALL_ERROR_LABEL /* Jump to error handler if error. */

/* Restore destroyed registers. */

movq %r12, %rsi

/* Restore the floating-point context. Not the registers, only the

rest. */

movq oFPREGS(%rsi), %rcx

fldenv (%rcx)

ldmxcsr oMXCSR(%rsi)

/* Load the new stack pointer and the preserved registers. */

movq oRSP(%rsi), %rsp

movq oRBX(%rsi), %rbx

movq oRBP(%rsi), %rbp

movq oR12(%rsi), %r12

movq oR13(%rsi), %r13

movq oR14(%rsi), %r14

movq oR15(%rsi), %r15

/* The following ret should return to the address set with

getcontext. Therefore push the address on the stack. */

movq oRIP(%rsi), %rcx

pushq %rcx

/* Setup registers used for passing args. */

movq oRDI(%rsi), %rdi

movq oRDX(%rsi), %rdx

movq oRCX(%rsi), %rcx

movq oR8(%rsi), %r8

movq oR9(%rsi), %r9

/* Setup finally %rsi. */

movq oRSI(%rsi), %rsi

/* Clear rax to indicate success. */

xorl %eax, %eax

ret

(The o* symbols are #define‘d in another file to be offsets into the

ucontext_t struct.)

You might spot a few unnecessary things here:

- Argument registers (RDI, RDX, RCX, R8, R9 and RSI) are saved and restored even though the calling convention doesn’t guantee that they’re saved and restored

- x87 and SSE state is saved and restored, even though we’re not doing anything with floats or SIMD where register contents need to be preserved across function calls

- The signal mask is saved and restored with the system call

sigprocmask, even though the signal handlers in RethinkDB are the same globally

The final sin–making an unnecessary syscall–is the greatest, and eliminating this provides a big speed boost. On top of this, it helps to eliminate the memory traffic from saving and restoring the unnecessary registers.

Things that weren’t important

I made one minor optimization across all of these: stacks were malloc‘ed

rather than calloc‘ed, since there’s no reason that they have to be zeroed

beforehand. It turns out that this isn’t crucial to performance once pooling is

applied; it just reduces the warmup time. Reducing the size of the callstacks

is similar–with pooling, it just reduces warmup time. Without pooling, both of

these optimizations yield significant improvements in throughput. It still

might be a good idea to have small callstacks so that they don’t take up too

much memory, but this is not a problem right now. In practice, warmup time will

be dominated by disk I/O in filling up the in- memory cache, and the database

will be restarted only rarely.

Conclusion

Coroutines can be made to work fast, though it’s not as immediate as one might hope. The POSIX primitives aren’t optimal for all applications. I’d like to thank Andrew Hunter for giving me advice on how to proceed in this optimization process.

RethinkDB Team

RethinkDB Team